Unlike Peter Thiel and Giorgia Meloni, I did not grow up with “The Lord of the Rings” in my life, and, reading it now with my son, it’s hard to pinpoint what about it he finds so entrancing. (Occasionally, when Tolkien gets going about Balin, son of Fundin, and Aragorn, son of Arathorn, I have to turn away from my kid and carefully suppress a yawn.) The entertainment value of the “Harry Potter” books, which are among the most tightly plotted confections ever sold, needs no explaining. “Harriet the Spy,” a subtly acerbic sendup of Manhattan socialites as seen through the eyes of their emotionally neglected children, holds up shockingly well. But “The Lord of the Rings,” despite all that I’d heard about dark magic and epic battles, is mostly about walking through the forest. As one popular plot synopsis on TikTok goes, “Walk, walk, hide, walk, walk, walk—steal some mushrooms!” My son watched the TikTok and laughed, conceding the point, then went back to reading. (“The Company filed slowly along the paths in the wood, led by Haldir, while the other Elf walked behind.”) I lay down next to him, taking the book from him and starting to read aloud. (“The Company marched on, until they felt the cool evening come and heard the early night-wind whispering among many leaves.”) And after a while, almost despite myself—“He laid his hand upon the tree beside the ladder: never before had he been so suddenly and so keenly aware of the feel and texture of a tree’s skin and of the life within it”—I felt the hypnotic lull overtake me, too.

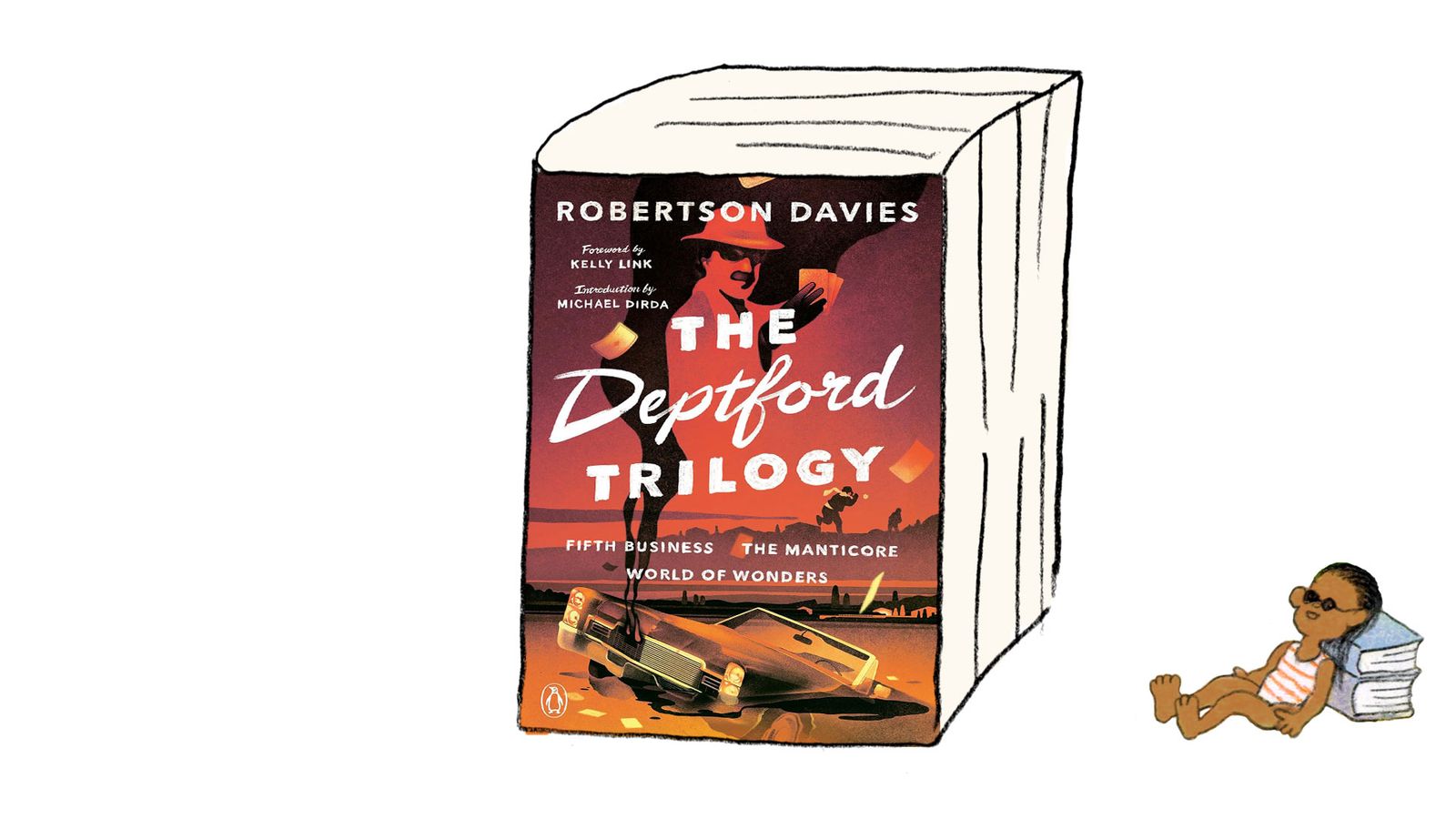

Katy Waldman on “The Deptford Trilogy”

Freud is out, Jung is in, and, this summer, you might treat yourself to Robertson Davies, a devotee of the psychotherapist, who would have approved of Davies’s belief that the best books afford an “exploration, extension, and reflection of one’s innermost self.” “The Deptford Trilogy,” which consists of the novels “Fifth Business,” “The Manticore,” and “World of Wonders,” traces the consequences of a seemingly small act of boyish violence. On December 27, 1908, Boy Staunton (a literal boy, double-underlining Davies’s interest in archetypes) throws a snowball with a stone concealed in it at his friend Duncan. He misses, and instead strikes a pregnant woman who goes into premature labor. Afterward, the woman’s mind dissolves and an ethereal simplicity sets in; Duncan, the snowball’s intended target, believes that she may have developed miraculous powers. He has grown up to become a respected hagiologist, and is narrating the first volume of the series in testy reply to a newspaper article about his retirement that cast him as a middling figure. Now, as he surveys his own life and the fate of Boy (mysterious, grisly) and other participants in that childhood scene, he wonders about his role in their collective drama—was he hero, villain, confidante, or, perhaps, the fifth business, the slippery extra who brings the story to a close?

“The Manticore” picks up the thread with a new narrator, David Staunton, son of Boy. He’s a rationalist lawyer who sentences himself to Jungian analysis after the death of his father. In Davies’s hands, the interpretation of dreams becomes swashbucklingly grand, mystical, beautiful, and grotesque. “World of Wonders” centers on one of the earlier books’ most enigmatic personalities: Magnus Eisengrim, illusionist extraordinaire, who unfolds secrets of his own.

I read these books when I was a teen-ager and was floored by their intensity and grandeur. Rereading them now, drowning in text—and specifically in voiceless text, with no human behind it—I love their talkiness. Davies’s characters are mesmerizing speakers, who live to spar, lecture, and lie. They’re old-fashioned and pretentious and peevish, and they hold forth about everything from theatre to polyamory to the nature of the Devil. Their speeches, at their headiest, inspire hope and a kind of holy terror. (“In short, Davey, God is not dead. And I can assure you God is not mocked.”)

Jennifer Wilson on “War and Peace”

The translators of “Gaza: The Poem Said Its Piece,” by the Palestinian poet Nasser Rabah, were relieved when, after a period of no contact with Rabah and his family, they finally received word last winter that he was alive. The news was bittersweet, coming via a video clip of Rabah, surrounded by the rubble of his home library in Gaza, pulling a book from the debris: “War and Peace,” by Leo Tolstoy. It’s a novel I first read in college, and have thought back on frequently in the past year and a half as images from Israel’s assault on Gaza and the ensuing humanitarian crisis have sat strangely on my social-media feed alongside reactions to celebrity gossip and debates about the state of book reviewing.