Writing in this magazine in 1973, Kennedy Fraser referred to style as “individualistic, aristocratic, and reckless,” and one or all of those qualities can be seen in the various personalities whose sartorial choices are featured here, including the fantastic, in all senses of the word, Julius Soubise, an eighteenth-century dandy who was born into slavery in the Caribbean and more or less adopted into the aristocracy in England; the stately young W. E. B. Du Bois, dressed to the nines, in 1900, at the Paris International Exposition, for which he organized a groundbreaking exhibit on the Black condition in the U.S.; and the late journalist, creative director, and Vogue editor André Leon Talley, in a Polaroid from the nineteen-seventies, draped in an African robe and sporting a multicolored kufi. But to see these flourishes, no matter how entertaining, as only flourishes would be wrong. Miller is aiming at something deeper and more elusive.

Style, Fraser noted, is not merely a matter of elegance or taste: “it is more akin to a philosophy, and it is surely closer to an art.” But how do you resist the urge to anthropologize or mummify it in a museum setting? Especially one as large as the Met, where aesthetics and anthropology often go hand in hand? And how do you discuss the ways in which the history of race has affected and fuelled the elusive progress of style, which depends on change to keep itself alive? Part of what makes “Superfine” work is the fact that Miller doesn’t turn away from these questions; instead, she gives us a synthesis of possible responses to them.

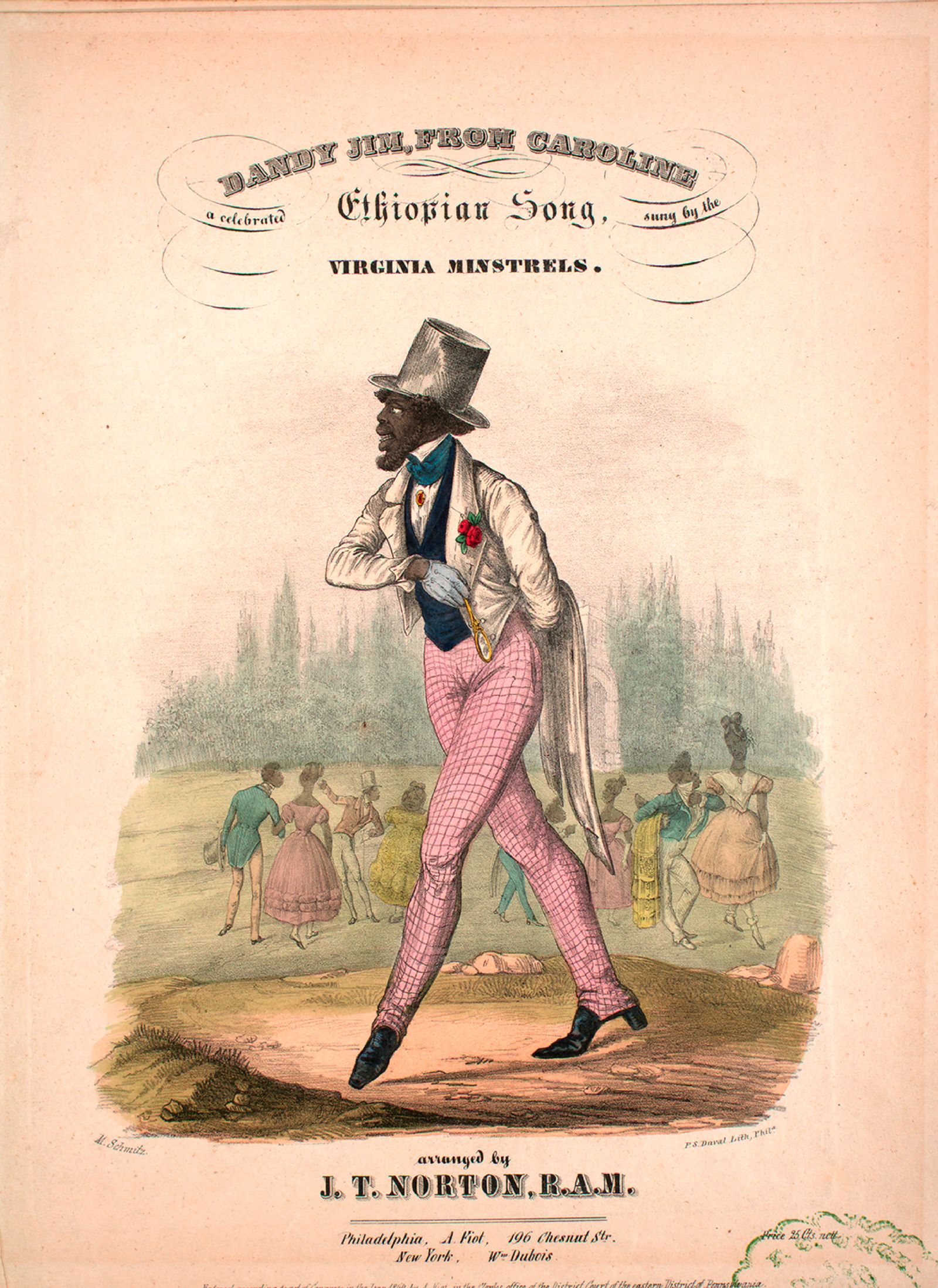

Cover image of the sheet music for “Dandy Jim, from Caroline: A Celebrated Ethiopian Song,” arranged by J. T. Norton, printed in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1844.Photograph from Sheridan Libraries / Levy / Gado / Getty

In her essential (if unfortunately titled) “Slaves to Fashion,” a study of the Black dandy and what she calls “black diasporic identity,” Miller argues that “stylin’ out” has been a fact of Black American life for centuries. For many enslaved people who had escaped or been freed, she notes, fashion was “practically and symbolically important to a . . . sense of individuality and liberty.” “Stylin’ out” has never been just about dressing up. It is a way of showing yourself and your community that you’ve survived another day. To dress in whatever constitutes your best, and displays your sense of self, honors the body in a way that the world often doesn’t. In our puritanical nation, which has a complex, often crushing relationship to difference, “stylin’ out” was and remains an act of resistance.

But America wasn’t on my mind when I first entered the show’s dark, moodily lit space; France was. Not the France of Charles Baudelaire, who, in 1863, famously wrote about the dandy’s “burning need to create . . . a personal originality,” but the France I encountered a number of years ago when I visited the Church of Saint-Sulpice, in Paris—how struck I was by the church’s dramatic lighting, as priests walked in and out of the shadows, amid statues depicting Christian suffering. “Superfine” ’s lighting is similarly dramatic, and has a reverential feel, too, that evokes Baudelaire’s claim that dandyism is an act of faith practiced by “a weird kind of spiritualist.”

Designed by the artist Torkwase Dyson, the exhibition occupies nearly ten thousand square feet; as expansive as it is, you’ll find yourself wishing that the Met had devoted even more space to it. Rather than gallery-standard white walls, the show has unconventionally angled surfaces painted in shades of black and gray; it looks like a night sky filled with stars. The mannequins are a deep, almost silvery black, and we see them standing on platforms and on pedestals placed high on walls which give the impression that they’re floating, like well-dressed apparitions, above the scene. Dyson has a collagist’s eye, and that, along with her love of elegant carving and her tactile relationship to her materials, reminded me of the sculptor Louise Nevelson’s late public sculptures. Nevelson’s strong vertical forms, often painted black, can throw off your perception of the horizontal, which is to say the earth that they and you are standing on.

But you won’t stand still for long in “Superfine.” The show has a structure that Miller borrowed from Zora Neale Hurston’s essay “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” a fantastic, vexing piece, from 1934, in which Hurston talks about such aspects of Black life as “Culture Heroes,” “Originality,” and “The Will to Adorn.” Miller has divided “Superfine” into single-word concepts that pertain specifically to the Black body: “Ownership,” “Presence,” “Distinction,” and “Disguise” are four of the twelve titles that delineate the show without interrupting its flow.

On the afternoon I went, I started with “Ownership,” which features an exquisite piece from the Meissen porcelain factory. Titled “Lady with Attendant” (c. 1740), it shows a liveried Black servant offering a woman, presumably his owner, a cup of tea or coffee. The two figures gaze at each other with a look of mutual admiration, and although the characters are fictional, a lot of sad and familiar facts went into the making of this object. In eighteenth-century Europe, it was the fashion among the rich to dress their Black servants in what they thought African style might be—turbans, earrings, feathers. All those exotic things, including the servants’ black skin, of course, served the purpose of enhancing the “pure” whiteness of the Europeans. Looking at this piece, I recalled a lamp that some relatives of mine owned when I was a boy. The base was a knockoff of a knockoff of a Meissen piece that showed a similar scene: a Black servant and a white woman frozen in a loving glance. I remember thinking about how delicate that lamp was, on so many levels, and wondering how long it would be before someone smashed it.

Clothing by the contemporary designer Marvin Desroc.Photograph © Tyler Mitchell 2025 / Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art

As I continued through “Ownership,” the devoted expression of the Black figure in “Lady with Attendant” soon turned to recalcitrance. The refusal of the Black men represented in the show to be anything less than a self was clear in the stories of Soubise and others, who did not so much erase their past as make a spectacle of their present. Born to an enslaved mother in St. Kitts in the seventeen-fifties, Soubise was ten when he was presented as a gift to the Duchess of Queensberry in London—the Meissen piece come to life. Eventually, the Duchess freed Soubise but kept him on retainer; her patronage allowed him to live a life of privilege in elaborately furnished apartments, socializing with the nobility, going to the opera, and so on. Of course, his privilege was intolerable to some, and he was caricatured in the press. Still, “despite his perceptible social agency,” Miller writes in the show’s beautifully produced catalogue, “Soubise left relatively little historical evidence of his own—the fate of so many Black dandies to follow.” Writing history is not the same as living it. And the dandy lives, always, in the drama of the now, even if, or especially if, that now appears unable to contain him.