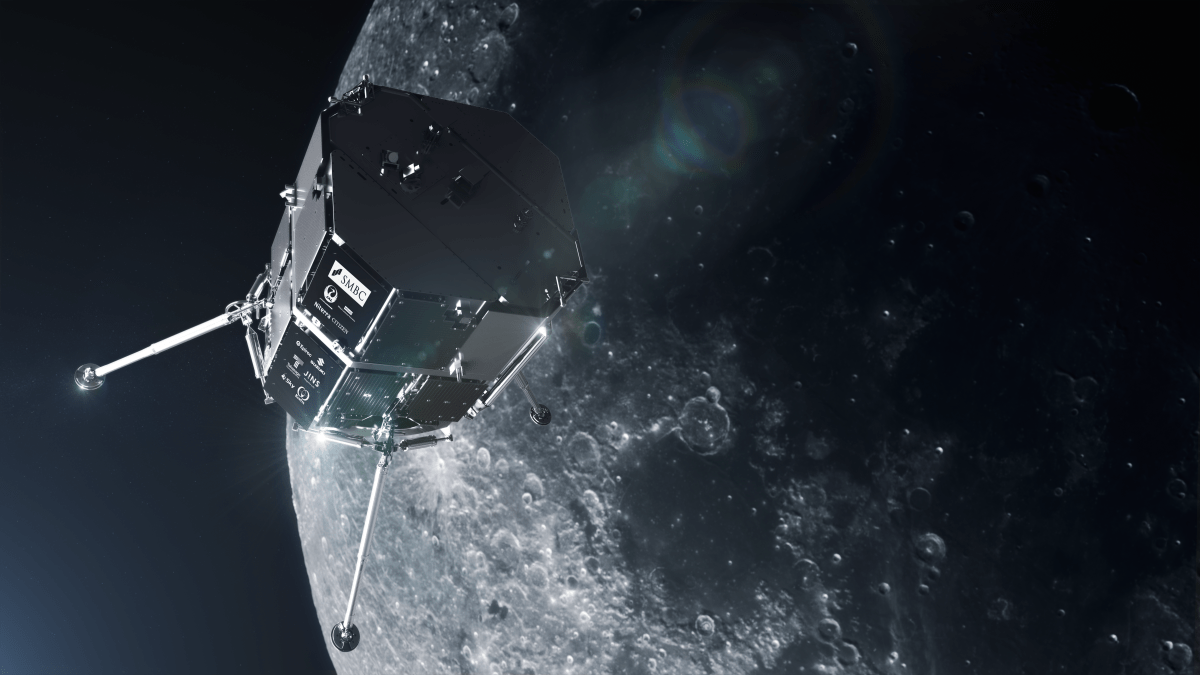

Europe likely just suffered a setback in its attempt to reach another milestone in the commercial race to use lunar resources. Tenacious, which was set to become the first European-made rover to land on the Moon, was aboard a lander that lost contact during its landing attempt — a strong sign that something went wrong.

If confirmed, this would be the second failed mission of the HAKUTO-R commercial lunar exploration program, two years after a previous crash that had already shattered hopes.

This loss will be particularly felt in Japan; ispace, the company behind HAKUTO-R and the currently missing Resilience lander that carried Tenacious, is a publicly listed Japanese company. But it is also a blow to Europe: The European Space Agency (ESA) supported the mission; and the rover was designed, assembled, tested, and manufactured by ispace-EUROPE out of Luxembourg.

Luxembourg isn’t just ispace-EUROPE’s base — it’s the reason the entity was created in 2017. As part of its SpaceResources.lu initiative, the tiny country became the second in the world after the U.S. to adopt a law giving companies the right to own resources extracted from space.

Had Tenacious’ Luxembourg-based operators managed to drive it around on the Moon, the rover would have captured video and gathered data. One of its missions would have been to collect lunar soil, called regolith, as part of a contract with NASA, to which it was supposed to transfer ownership of the samples.

“I think this will be very helpful to nail down what it means to commercialize space resources and how to do this on a larger scale, both in terms of volume and of global participation and coordination,” ispace-EUROPE CEO Julien Lamamy told TechCrunch on the eve of the landing attempt.

Winning such a contract from NASA was also a first for a European company. But it took some coaxing to get Lammy to brag about the agile team of 50 people from 30 nationalities that made this unique little rover.

Despite a resume that includes time at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory and MIT, Lamamy is not one to boast. In our conversation, he admitted he had to “channel his inner American” to explain his team’s achievements. But that’s also because ispace is willfully collaborative.

For instance, the lightweight scoop that was meant to collect regolith for NASA was made by Epiroc, a mining equipment provider out of Sweden. “We could have done this ourselves. Instead, we saw the opportunity to engage a terrestrial industry to think about space,” Lamamy said. “The more people participate, the better.”

More people are participating in Luxembourg’s space ecosystem, too. The Luxembourg Space Agency (LSA) was established in 2018, and the country actively supports the sector, which has gone from niche to mainstream since the Space Resources Law was adopted.

“Even better than that, there are many companies now established downstream of ispace in the value chain,” Lamamy said. He cited the example of Magna Petra, a startup partnering with ispace on mining Helium-3, a rarefied resource, from the lunar surface.

“Our ambition is to develop a space sector that is highly integrated with our industries on earth and opens up new market opportunities, both in space and on Earth,” Luxembourg’s Minister of the Economy, SMEs, Energy and Tourism, Lex Delles, said in a comment when ispace-EUROPE announced the completion of its rover.

That ambition is being fueled by money. Tenacious was developed with co-funding from the LSA through an ESA contract with the Luxembourg National Space Program, LuxIMPULSE. Tax incentives or direct aids are available both for startups and for multinational companies, according to research from Deloitte on Luxembourg’s space industry.

An unusual payload

Tenacious was designed to be both small and light, weighing about five kilograms — half the weight of NASA’s Sojourner Mars rover. By selecting mass-efficient and power-efficient components, Lamamy explained, his team was able to build a very small system that is cheaper to manufacture and to send to the Moon. This made its payload inherently limited, but designed to reach up to one kilogram.

As part of the Resilience mission, Tenacious’ payload included the scoop required for the NASA mission, and perhaps unexpectedly, a miniature red house. Known as The Moonhouse, this small sculpture of a Swedish cottage was supposed to symbolically become the first house on the Moon, a project that artist Mikael Genberg has been pursuing since 1999.

“It’s not about science or politics, it’s about reminding us of what we all share — our humanity, our imagination, and our longing for home. A red house gazing back at “The Pale Blue Dot”, as Carl Sagan once described our fragile planet,” The Moonhouse’s site stated.

Lamamy’s team had prepared to be in charge of successfully dropping and photographing The Moonhouse in a good spot, and took the role seriously. As part of the rover testing it conducted on Earth, both on its testing site in Luxembourg and in several European locations including Spain’s Canary Islands, the operators had rehearsed the procedure several times.

Although poetic, this may have seemed less of a priority than NASA, but not to Lamamy. “That’s an interesting paradigm shift; yes, we’re going to the Moon to improve our knowledge of the Moon from a scientific and commercial perspective, but we are also there to open access to artists, entrepreneurs, educators, and that’s also a very exciting element to the mission.”

Unfortunately, this will now likely have to wait.