The storage space was packed with thousands upon thousands of photographs. Some were at least a century old, imprinted on glass plates. There were others on nitrate film so deteriorated it was at risk of combusting.

In a blues and gospel mecca like Memphis, several faces were instantly recognizable: B.B. King, Mahalia Jackson, W.C. Handy. But much of the rest belonged to middle- and working-class Black Memphians on days when they might have most felt like stars. On display were weddings, graduations, fraternity parties and sporting events. In one photo, a group of homeowners tossed their mortgage papers into a fire, a celebration for climbing another rung on the ladder of upward mobility.

For more than 40 years, this trove of work by the Hooks Brothers Studio, once the go-to photographers of Black life in a city renowned for it, had been largely hidden away.

But now a painstaking process to preserve the studio’s archives — possibly more than 75,000 images — has begun. It will take years to complete. Decades, most likely. Still, those invested in the visual history of the city believe it is a worthwhile endeavor with the potential to deepen Memphis’s understanding of itself.

“It’s a priceless inheritance,” said Andrea Herenton, who purchased the collection with her husband, Rodney, before handing it over to the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art and the National Civil Rights Museum for preservation. She added that by leaving storage, the collection would be able to “inspire and live and breathe and teach and connect the past to the present.”

Parts of the collection illustrate Memphis’s proud history as the spiritual, cultural and commercial capital of the Mississippi Delta region, where rock ’n’ roll was born and the blues flourished.

Yet it is the quieter, more quotidian scenes that can serve as a counterbalance to the narrative of a Memphis withering in the shadow cast by the assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. Over time, poverty grew more entrenched; crime and violence became pervasive. Neighborhoods that once embodied prosperity and possibility for Black families were neglected.

The photographs by the Hooks brothers — vividly, joyfully — show something else.

“People still found their way through tribulation,” said Russell Wigginton, the president of the National Civil Rights Museum, which is housed in the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, where King was shot.

“That is the strength of this community, despite the poverty, despite the historical challenges,” Wigginton said. “There’s no party like a Memphis party. There’s nothing like when people are in community here, trust me.”

Henry A. Hooks Sr. and Robert B. Hooks opened their studio on Beale Street in 1907, when the area was still a bustling hub for Black residents in a segregated city, not yet a tourist destination filled with bars and gift shops. They had learned photography from James P. Newton, the first Black professional photographer in Memphis, and they had also studied painting in their youth, developing an artistic flair that informed their portraiture.

Their subjects included Booker T. Washington and Robert R. Church, a real estate entrepreneur who became one of the wealthiest men in Memphis. After moving their studio to a different location, the brothers eventually handed it off to the next generation: Robert’s son Robert Jr. and Henry’s son Charles took over and adopted more of a documentary style. Another of Robert’s sons, Benjamin, became the longtime executive director of the N.A.A.C.P.

Over the years, some feared that their archive would be lost and that the artistic legacy of the Hooks brothers would have to live on through the photographs saved in dusty yearbooks and albums. That piecemeal existence might have been a testament to how treasured individual images were, but it would fail to convey their collective influence.

“It’s just so unique in terms of being such a long-term visual documentation of one community, one city,” said Earnestine Jenkins, a professor of art history at the University of Memphis.

For Jenkins, like many in Memphis, it also represented something deeply personal. She pulled out a photograph from 1937. It was her mother’s class photo from the eighth grade, which had been taken by the Hooks brothers.

“It documents you,” she said of the collection. “It documents your family. It documents your community. It documents your region. It documents Memphis.”

Leaders at the two Memphis museums hope the public can help identify people in the archived images and offer context and stories about them. C. Rose Smith, an assistant curator of photography at the Brooks Museum, has been going to senior centers and alumni gatherings, successfully finding some people who had been photographed by the Hooks brothers.

The museums have expansive ambitions for the collection, including traveling programs and new works by artists who are using the images as inspiration. The first exhibitions are scheduled to open next year at both museums.

But a lot of work needs to be done first.

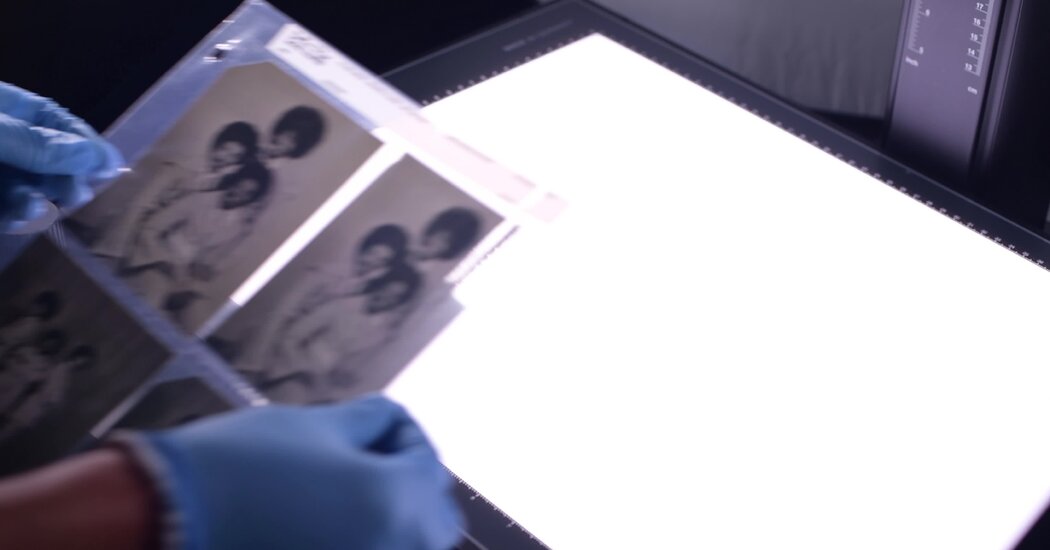

The bulk of the collection has been moved to a dark, quiet corner of the Brooks Museum, where Smith carefully evaluates prints and negatives on film and glass plates. Smith is drawing on their training as a photographer, cataloger and image specialist for museums, and even for the Atlanta Police Department, where they handled crime scene photos.

“It’s really thinking about line, shape and form,” Smith said. “It’s thinking about contrast. It’s thinking about the beautification of a Black subject, and how the Hooks brothers may have even manipulated lighting to make sure they’re able to render Black skin tones correctly.”

Smith also looks closely at the people in the photographs — the fashion, the poses, their bearing. The images, particularly portraits, reflect how they wanted to be seen and immortalized.

The project’s timing has been fortuitous. Like many other regional art museums, the Brooks Museum has been trying to forge stronger relationships with a more diverse slice of the population it serves. Museums long centered their mission on preservation, a priority that is evident all the way down to the Latin roots of the word “curate,” said Zoe Kahr, the museum’s executive director.

“It was all about the object,” she said, “and we’ve shifted from prioritizing the object to prioritizing the community.”

That philosophical transformation has inspired art-making community events and an aspiration to some day have free admission. It also informed the design of a new facility that the museum is scheduled to move into next year.

The museum’s longtime home, originally constructed with Georgian marble and set in a sprawling city park, could seem like a fortress guarding its contents; the new downtown building will have public spaces as well as walls of glass that allow art to be viewed from the street.

After Smith picks possible photos for the first Hooks Brothers exhibitions, they give them to Lauren Killingsworth, a collection specialist, to be digitized and recorded. She carefully lines up the images and then photographs each one with a digital camera attached to a stand. Some days, she can get through 50, maybe even 100 images. Then there are the days where it is only a handful.

The immediate goal is to have images ready for next year’s exhibitions. But the employees know that the preservation project could fill the rest of their professional lives.

“Thirty years!” said Smith, offering one educated estimate for how long the project could take, and noting they had recently turned 30. “OK, we’re going to be 60!”

Smith was not daunted. They are a Memphis native. Photographs of their grandmother and great-aunts are in the archive. This was a chance to be part of important history, and they planned to stick with it.

“For however long this takes,” they said.