April in Paris has nothing on May in New York. Spring happens to the city as everything happens here: not at all, then all at once. The forsythia skims the crosstown buses as they swerve through Central Park, and the daffodils dare dogs, from every tree bed, to do their worst. Magnolias unfurl their petals to flaunt their fancy two-toned manicures. Cherry trees blush all over town. On Park Avenue, the tulips are out, orderly and abundant, as they are at corner delis and bodegas, cooling their stems behind heavy plastic curtains. Long strands of pollen drift down from sidewalk oaks, dusting parked cars greenish gold. Birdsong, jackhammers, and sneezes, the sounds of the season.

Now the fauna stirs and molts. From Wakefield to Tottenville, members of the native population emerge from hibernation to sun themselves on stoops and benches. Winter coats are stuffed deep into too-small closets. Construction crews rumble every neighborhood. Playgrounds shriek to life; teen-agers bump backpacks and kiss on street corners. The city, forever in a rush, adjusts its pace, remembers how to stroll, to saunter. Would you believe that the Yankees started the month first in their division, and the Mets in theirs? The Frick is open and resplendent again. Audra McDonald is on Broadway, singing Mama Rose. This is the optimistic time, when New York’s too-muchness and its not-enoughness hold in the briefest balance—the cup-filling weeks, when those of us wedded to this city for richer or poorer, by choice or by chance, renew our vows.

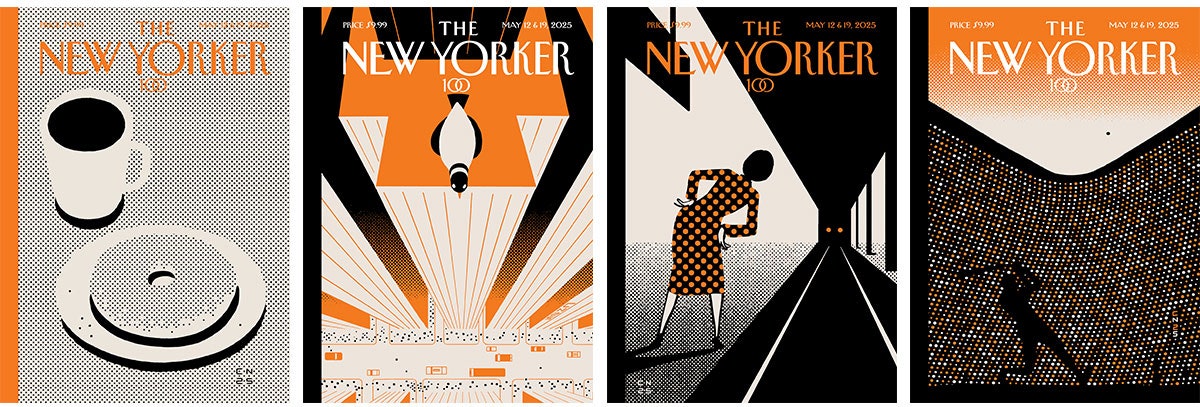

New York: A Centenary Issue

Subscribers get full access. Read the issue »

Covers by Christoph Niemann

A hundred years ago, when this magazine was founded, the Chrysler Building had not yet been built. The old Waldorf-Astoria still stood on the stretch of Fifth Avenue that is now home to the Empire State Building. Greenwich Village was thick with activists, artists, and anarchists; Harlem was having its Renaissance. So, really, was the whole town. Between the turn of the century and the start of the Great Depression, the population doubled, making New York the largest city in the world. A four-room apartment in Chelsea rented for forty dollars a month, which, if you do the math, works out to less than eight hundred dollars today. Don’t do the math.

New York had its own gravitational pull then. It still does, whatever the rent. Other cities have better infrastructure, fewer rats, cleaner streets, plentiful public toilets, more elbow room. Yet people continue to flock here. They come to make art, money, trouble, love, a name. They stay because they can imagine being nowhere else. This is the mythos of the city, the Frank Sinatra version that plays at the stadium after the ninth-inning walk-off home run. But, because it’s true—because New York’s “essential fever,” as E. B. White called it, burns on, through bankruptcies, terrorist attacks, epidemics and pandemics, boom times and busts—it endures.

New York abides by its own set of Newtonian laws. For every complaint that someone makes about the city, someone else has an equal and opposite complaint. New York is too fast. (Spare a thought for the mother struck down with her children on Ocean Parkway by a reckless speeder on a sunny Saturday afternoon in March.) It is too slow. (The next train is coming in eighteen minutes.) It is too empty. Up in the sky, the apartments in the gleaming towers of Billionaires’ Row sit idle while their owners decamp to one of their other homes, thousands of miles away. It is too full. In the past three years, more than two hundred thousand migrants have sought refuge here. Far underground, women who have come from the only homes they knew, thousands of miles away, walk from subway car to subway car, selling chewing gum and candy bars, babies strapped to their backs. Eric Adams, who last year made New York history in the competitive category of executive corruption by becoming the first sitting mayor to be indicted on federal charges, claimed that they will “destroy” the city, yet the city still stands.

Remember What Used to Be Here? is the New Yorker’s favorite game. We hate to see our private maps overwritten. Shed a tear for the lost favorite bar, the all-night bagel shop that became a cellphone store. Stasis is not in the character of the place. The city in motion stays in motion. Sometimes the change is even for the better. Paid family leave and 3-K, compost bins and congestion pricing: at last, and amen!

Other changes merely baffle. The other day, passengers taking the F train from Brooklyn into Manhattan discovered that it had metamorphosed, like something out of Ovid, into a G train to Queens, without so much as an incomprehensible crackle of speaker static. The passengers, breaking the pact of benign disregard that passes here for privacy, turned to one another. Fate and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority were cursed. Ubers were called. Then, finally, Manhattan rose across the East River, all chrome and haze from the smoke drifting in from the wildfires choking New Jersey, and the whole crazy place was forgiven again.

There’s no greater pleasure in this town than observation, and you can do that for free. A group of high-school girls identified by their red softball jerseys as the Kennedy Lady Knights, from the Bronx, ate slices of pizza while they waited to cross Delancey Street. On Rivington, a poster called Andrew Cuomo a crook. A gray-haired woman marched alone the wrong way down a Christopher Street bike lane, brandishing a sign that read “hope over fear.”

That’s the right motto, isn’t it, for these times? “The intimation of mortality is part of New York now,” White noted, in 1948. He was referring to the new danger of nuclear war. Forty-five years after the city’s first known aids death, twenty-three years after the World Trade Center fell, five years after the all-night sirens and mobile morgues that came with the coronavirus, it is painful, and infuriating, to think that the greatest threat the city currently faces originates from one of its own. The President has Columbia University in his sights, and he won’t stop there. New York’s status as a sanctuary city is under attack. Immigrants are the very heart of this town; if this spring is more silent than it should be, it is from the fear that has kept people indoors. No city is more celebratory of the individual. No city depends more, for its soul, and its survival, on the collective. “No one should come to New York to live unless he is willing to be lucky,” White wrote. He was right. But, together, we make our own luck. ♦